Skull Scanning

Kerry Grens

DECEMBER 20, 2008

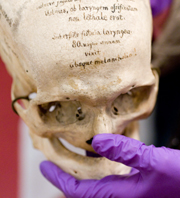

- A skull from the Mutter Museum

- (Todd Vachon/WHYY)

- View the Slideshow

Web Resources

- Mutter Museum

- Janet Monge at the University of Pennsylvania

- Tom Schoenemann at James Madison University

- WHYY's Health and Science Desk

Related Stories

- Good News, Bad News, No News

- Spending the Stimulus Money

- Foreclosure Double Punch

- The End of Weekend America

More From Kerry Grens

For years, anthropologists have wanted to do research inside the heads of human skeletons to answer questions about the evolution of the brain. They also wanted to figure our how ancient skulls are different from modern ones. The problem is getting inside the skull without cracking it open. This weekend, researchers in Philadelphia are getting their chance. They are taking skulls from a museum to a hospital and CAT scanning them. These 19th-century bones are part of a collection at the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia - a medical history museum specializing in what the curator calls a "disturbingly informative" collection. From public radio station WHYY, Health and Science Reporter Kerry Grens brings us the story.

---

The Mutter Museum is not one for the squeamish. Deformed fetuses float in jars. Gruesome, antique dental and birthing equipment are on display. And then there's the museum's centerpiece: A wall of row upon row of human skulls - 139 of them.

On a Friday afternoon, a group of EMTs-in-training admire the skulls. "When I first walked in and saw them it was kind of hard to bear," admits Carlos, one of the EMTs, as he reads the information cards describing who each of the skulls came from. "A lot of these skulls must have suffered a lot of pain before they passed on," he adds.

"What you're seeing here is people who either died in battle, were executed, suicide, sometimes died of smallpox," explains Anna Dhody, the museum's curator. Earlier that morning, Dhody carefully plucked one skull from the shelf. "Here we have Julius Farkas, age 28, a Protestant soldier," she explains. Farkas died of "suicide by gunshot wound of the heart because of weariness of life."

There's a tightrope walker who died of a broken neck. A famous Viennese prostitute, a child murderer, a man who died of self-castration. Dhody hands each of these skulls to Janet Monge, an anthropology professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Monge is packing the skulls in bubble wrap for their CAT scanning field trip across town. Monge delights in the peculiarities of each skull, looking for variants.

The skulls' bodies, unclaimed or rejected by the church for burial, ended up in the hands of Joseph Hyrtl in Vienna in the 19th century. Hyrtl was a doctor and anatomist who had agents around Europe collecting skulls in an efforts to disprove phrenology - the practice of interpreting a person's personality by the bumps on his head.

Bones weren't collected from regular everyday people. "Often you get a lot of criminals and people who did unusual acts," explains Monge. "You're not going to see noblemen or wealthy merchants," says Dhody.

Hyrtl had short biographies for each person penned in meticulous cursive right onto the bone - preserving their stories forever. According to Dhody, it's what makes the collection so rare. "This [is a] known population. And to have one that is predominantly European is definitely a benefit."

For the first time, Janet Monge will have Europeans in her growing catalog of digital skulls. Several years ago, she started CAT scanning skulls mostly from Asia and South America. Now, the first round of Hyrtl skulls were packed up and moved over to the hospital at the University of Pennsylvania last weekend to expand Monge's geographic spread. Before dawn last Sunday, Janet Monge and her colleagues wheeled their precious cargo in a rubber cart across 34th Street to the hospital.

Monge hasn't just been scanning skulls; she has a whole digital library of human bones. She is making this virtual museum freely available to any researcher who wants it. At the hospital, we meet up with Monge's colleague, Tom Schoenemann. He's been involved with her scanning project since it started a few years ago. The big mystery Schoenemann is interested in solving now is how the human brain evolved.

"If you want to study brain evolution," explains Schoenemann, "you have to look in the past and the inside surface of the brain case. It's a very complicated odd shape, and if you want to� get some idea of how brains have changed over time, you have to figure out how to make sense of that and compare them in a quantitative way."

It's not so easy to measure the size of the inside of a skull. Traditionally scientists would fill it up with shot or bird seed, then measure the volume of seed it took to fill the head. With CAT scanning, sizing a skull is much more accurate. Some parts of the head, like the inner ear, are locked within the skull and can't be studied without destroying some bones. CAT scans leave everything intact - and they show all.

Instantly, on the computer screen in the CAT scan room, Monge can stare straight into the inner ears of one of the skulls. She says she'd like to use these images to study how human ear bones changed shape to accommodate us as we evolved to stand on two legs. But her primary interest is human variation - or the range of normal humans. She's morphing all her skeletal scans into one database that will average the range of human dimensions around the globe and throughout history. That way, if she has a rare archeological specimen, like an extremely small head, she can determine whether it falls in the range of normalcy or if it is something unique - like a person with a disease, or even a non-human.

With the old method, a skull could take nearly a day to measure. "This way," says Monge, "we can virutally extract all the information within seconds."

And in those few seconds, the skulls of lovesick Julius Farkas and the others in the Hyrtl collection will become more than just a display of 19th-century outcasts. They will be part of a skeletal library defining what is normal among humans.

Monge is looking forward to analyzing the entire Hyrtl collection. She says Doctor Hyrtl helped preserve the skulls' unique, individual stories. Now she's going to tell their shared, biological ones.

Comments

Comment | Refresh

From San Diego, CA, 01/16/2009

Hi, what was the music you played right before this story? Thanks, Loraine

From west point, CA, 12/22/2008

I believe the skull scanning project was begun by Dr. Schoenemann, working on a grant he received for that purpose from NIH

From River City, CA, 12/20/2008

12/20/08

Nutritional Dietary deficiencies such as those contributing to rickets and stunted growth of bones and general anatomical structure are also contributing factors in bone structure, size and malformations. Occipital lobe underdevelopment resulting from nutritional and chemical intrusions may at first appear to evidence deficient mental function but the distinction between the brain and the skull in which it is encased remain a factor not always considered, although skeletal hindrances and latitude such as may be present in a skull does appear to at times influence personality as is appparent from the structure and size of the fingers. Usage of the thumb and the fingers has significantly added to human tool making abilities and ascendancy on the planet.

Post a Comment: Please be civil, brief and relevant.

Email addresses are never displayed, but they are required to confirm your comments. All comments are moderated. Weekend America reserves the right to edit any comments on this site and to read them on the air if they are extra-interesting. Please read the Comment Guidelines before posting.

You must be 13 or over to submit information to American Public Media. The information entered into this form will not be used to send unsolicited email and will not be sold to a third party. For more information see Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy.