Not So Bezerkeley After All

Krissy Clark

MAY 17, 2008

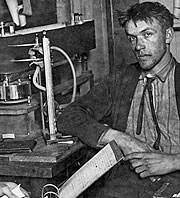

- First practical lie detector

- (Courtesy Berkeley Police Department Historical Preservation)

- View the Slideshow

Web Resources

Related Stories

- Spending the Stimulus Money

- Foreclosure Double Punch

- The End of Weekend America

- Conversations with America: Concluding the Conversation

More From Krissy Clark

This weekend, California gays and lesbians are setting their wedding dates -- the California Supreme Court ruled this week that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry.

Of course, there's a whole history that led up to this decision. But you can trace at least one of the roots all the way back to an ordinance passed by the Berkeley city council in 1984. Berkeley was the first city in the nation to provide health benefits for domestic partners of local government employees. That ordinance has become a model for cities around the country.

Those are just the sort of links that a new exhibit at the Berkeley History Center is celebrating. It's called "Berkeley: A City of Firsts," and Weekend America's Krissy Clark takes us there:

Berkeley can be one of those cities that the rest of Americas like to mock. Take one recent example -- on a sunny day in May not too long ago, when a group of pagan witches gathered in front of a U.S. Marines Recruiting Office in downtown Berkeley to protest the Iraq War.

A gleeful Fox News anchorwoman set the scene: "They are now casting spells for peace! Of course you know where they are... Berkeley, California!"

Or "Berserk-ly," as it's known in some parts. Or the "People's Republic of Berkeley."

Linda Rosen, a proud Berkley-ite herself, displays those nicknames in giant letters at the front of a new exhibit she's curated: "Berkeley, a City of Firsts." Rosen is out to prove that the rest of America actually owes a lot to Berkeley's civic innovations.

Rosen points to a black-and-white photo that opens the exhibit. "This is a picture of the police department, taken a little after 1908. They are so proud of themselves," she says. "I just couldn't resist but use that one, because they are just innovating like crazy."

It turns out that Berkeley, known more for its "innovations" in civil disobedience, is also an innovator in law enforcement.

Exhibit A: The lie detector. It was dreamed up in Berkeley in 1921, by the city's police chief. He also established America's first police academy, and recruited the first college-educated cops. "And everybody laughed at him." Rosen says. "'College cops! For heaven's sake!' The media made fun of him." College-educated cops are now commonplace around the country.

Berkeley also claims to be home to the nation's first gourmet coffee shop, opened by Alfred Peet (of Peet's Coffee) in 1966. Also, Berkeley was home to the first school crossing guard program, the first municipal off-leash dog-park, the first power-tool lending library, the first to grant benefits to same-sex partners of city-employees, and first can of pickles.

Actually, not the first can of pickles -- I made that one up. But Linda Rosen admits that it can be easy to go overboard when you're hunting for "firsts." She has had to correct some displays herself since the show opened a few weeks ago. After further research, Rosen discovered that Berkeley was not the first city to put curb-cuts in sidewalks for the disabled. "We came after Kalamazoo," she whispers. Nor was Berkeley the first to do curbside recycling, or declare themselves a nuclear-free zone, as some residents had once claimed.

Berkeley's innovations in beer laws, however, are secure: "The Home Brew Victory Song," written by a folk-singer named Helen LaRoza in 1978, makes it clear:

We can now make beer in California!

They've legalized our brewing it at home!

The man behind the beer law was Tom Bates, who represented Berkeley in the California state Assembly for many years. Before his bill passed, home-brewed beer was illegal across the country, unless you first applied for a costly license ($828 in California) -- a vestigial law from Prohibition Days. In the early 1980s, Bates wrote legislation allowing home brewers to sell their beer on-site, and the national craze over "microbrew" was born.

Bates, who's now the mayor of Berkeley, enjoys his status as progenitor of brewpubs. When he and his wife (the former mayor of Berkeley) travel, they like to visit brewpubs around the country, and tell the story to the owners. "I've actually told them they should put my picture up like Col. Sanders," Bates says. "But nobody has done that yet."

Bates isn't shy talking about any of Berkeley's "firsts," and he gave the keynote speech at the opening of the History Center's exhibit a few weeks ago. He laughingly acknowledges that the show may feed into his city's occasional tendency toward self-importance. But Bates says the show is also an important reminder of how American society evolves.

"People say 'That's Berkeley -- there they go again,'" Bates says. "Well, guess what? Those trends and those ideas travel. They have legs. And eventually people say 'Maybe that's not such a screwy idea. Maybe we can do it!.' Other cities, middle America, enter in and then suddenly it becomes more and more conventional wisdom."

In other words: Watch out Wichita. In a few years, you too might have a ban on Styrofoam take-out containers, health benefits for domestic partners and a surplus of gourmet dog bakeries.

And so I called Brint's Diner, in Wichita, Kansas. I figured I should let someone in Middle America know about their impending future. Wichita already has a history of following in Berkeley's footsteps. They have a police academy, crossing guards and a tool-lending library. But is Wichita ready for California cuisine?

That's what I asked the owner of Brint's Diner, Jessie Medina. He has lived in Wichita all his life and has worked as a short order cook since 1964, when he was 15-years-old. When I called him, Medina had just finished his shift at the grill, and was about to sit down to a bacon cheeseburger with fried liver and onions, and a side of homefried potatoes.

So would he ever consider adding a little Berkeley flavor to his menu? Switching over to vegan entrees, perhaps?

Medina pauses. "No." Then he changes his mind. "I probably would if I had the clientele for it. But everybody loves grease down here."

I tell Medina about one of Berkeley's latest innovations: a plan to redesign utility districts to make it easier for residents to switch to solar power. Medina likes that idea. And what about the pagan witch anti-war protests?

"I don't think that would happen here," Medina laughs. "I'm just going by what I've seen, but my early customers, we have time to talk politics. Sometimes I'll agitate them. I'll take the counter-point, just to see what happens. Sometimes they'll start trembling. One guy starts sneezing."

Sneezing?

"Yeah. He can't stop," Medina says. "He always sneezes when he gets real upset."

Medina says his customers are almost uniformly old and conservative. But they're the nicest people you'll ever meet, he tells me.

"Come to think of it, they're a lot like the people in Berkeley. Real nice," he says. Medina knows, because he visited Berkeley once, with a friend, in 1971. He didn't have much money, so he lived on black coffee and apricots that he picked off a tree. He missed Wichita, and headed back home pretty quickly. But he'll always remember the hippies playing guitar on Telegraph Avenue.

Comments

Comment | Refresh

Post a Comment: Please be civil, brief and relevant.

Email addresses are never displayed, but they are required to confirm your comments. All comments are moderated. Weekend America reserves the right to edit any comments on this site and to read them on the air if they are extra-interesting. Please read the Comment Guidelines before posting.

You must be 13 or over to submit information to American Public Media. The information entered into this form will not be used to send unsolicited email and will not be sold to a third party. For more information see Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy.